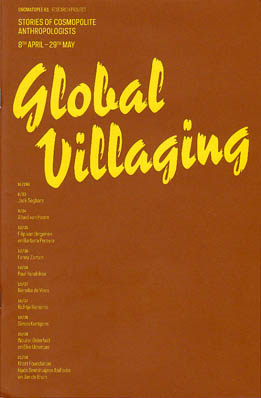

Text for exhibition catalogue Global Villaging in Onomatopee, Eindhoven in 2011. See for documentation exhibited work: Visual work > Drawing > Memories of Aleppo 2004 (2010). (Scroll down to read text.)

Memories of Aleppo

I took part in the International Women’s Art Festival in Aleppo, Syria, in October 2010. I had made drawings and texts titled Memories of Aleppo 2004, based on memories of my then stay of half a year. In 2004 I worked as an assistant to festival director Issa Touma on the International Women’s Art Festival and the International Photography Gathering.

Unfortunately Memories of Aleppo 2004 was removed from the festival by the authorities.

The festivals and exhibitions that Issa Touma hosts in his gallery Le Pont are extremely courageous in dictatorial Syria with its sovereign secret services. Syria’s inhabitants consist of numerous ethnic and religious groups, who are kept short by the secular government headed by president Bashar Al-Assad. State control is ever present.

The Syrian art world in European eyes seems old-fashioned and neat. Everything that could be confrontational for certain (religious) groupings is suppressed by superiors.

Touma on the other hand is not bothered by the taboos in Syria. He wants to show art that he finds interesting, and refuses to subject himself to the usual control and interference. In the exhibitions that he organises in conservative Aleppo, he shows art that you cannot find anywhere else in Syria, not even in the slightly freer Damascus. Criticism to the regime, nudity, sex, religion, work from Israeli as well as Palestinian artists – Touma shows it all. He is an exceptionally courageous cultural pioneer.

Politicians as well as the secret service have monitored him closely for years and bully and sabotage him whenever they can. Many people wonder why he has not been arrested yet. A possible explanation could be self-interest: the regime can get international credit by tolerating Touma’s cultural activities, as this allows for the illusion that the lack of freedom in Syria is not so bad.

The year I went to Syria to assist Touma, 2004, was disastrous. There was no end to the bullying and intimidations from the authorities and secret service. Consequently both festivals were prohibited and Touma’s gallery was closed and sealed for months.

In 2010 I returned. I wanted to show work about the alienation I had experienced six years before, about the threats and how watchful and cautious I started to behave. I walked around in a world of which I could only perceive the surface, even though I clearly felt that everything that mattered happened behind it. I could hardly decode the hidden terms and ambiguities.

Doubts about sensitive memories – like those about confrontations with the secret service – I put aside. In the worst case I expected a confiscation of my possessions and eviction. More difficult to predict were the possible risks for the festival and the Syrians involved. As a precaution I showed my work to Touma in advance. I hadn’t realised that he would be the last person to advise anyone to submit herself to (self-)censorship.

Apparently, making memories public could easily be compromising. I noticed six years ago, as well as now, that it is remarkable how quickly one internalizes censorship. A couple of months in Syria had been enough to get a glimpse of the cautiousness that must be second nature to Syrians. I too thought: am I allowed to do this? Who will come to watch, how could this be interpreted?

Naturally people who want to express their opinion in a dictatorship are seen as a threat. Possibly any type of emancipation starts with contemplation and analysis of personal experiences. An individual aiming to think independently will easily come into conflict in both personal as socio-political relations.

On arrival in Syria, my anxiety about the explosive potential of my work faded away when I saw the rest of the art work and shows of the festival. There were photos of Izabella Demavlys of Pakistan women, maimed acid by their husbands or family members; a world premiere exhibition of the photographs from Hengameh Golestan of the demonstrations in Teheran in March 1979, one day before women were restricted to wear veils in public; digital photomontages assemblies by Erika Harrsch of gigantic butterflies fused with vaginas.

The festival appeared a pattern-card of broken taboos. My work seemed hardly shocking in that context. Nevertheless, two workmen were ordered to rip my drawings from the wall. Two days later Erika Harrsch’s work was censored too.

We can only guess what the reason for the censorship could have been. The government doesn’t give an official motivation. It may have been the mockery of the drawings with references to the secret service; or the drawings of women veiled from top-to-toe, which featured the comment that some Syrians call them ‘ninjas’.

In fact, the censorship of my work may very well have simply come in handy in other people’s powerplay. The arbitrariness and opaqueness of the execution of censorship reveal something significant about its function. Where there are neither rights nor rules, just fear for cruel punishments, reigning is easy.

To be secure, people tend to restrict themselves under such circumstances. The fear for censorship incites self-censorship, and works preventatively. And because the ruling powers don’t have to answer to anyone, it is very simple for them to create a problem whenever it suits them in order to strengthen their positions or to undermine their opponents.

Fortunately, Erika Harrsch and I were able to show our censored work in Le Pont Gallery in a separate exhibition later on. Apparently the fact that the gallery was not a government funded festival location, but a private exhibition space, was very helpful. Despite the lack of public promotion, many people showed up. Censorship proved good promotion.

Translation: Ellen Zoete.